I first saw Jamel Shabazz’s photographs the way a lot of New Yorkers see the city’s most important work. Out of context. Uncredited. Just floating through the culture like a shared memory. An image in a book somebody left on a coffee table. A page passed around. A face on a train platform captured with so much presence it starts to feel like you once met that person, even if you never did.

Listen to Our Conversation

I marveled at his work long before I knew his name.

So sitting across from him at a chess table in the middle of Brooklyn felt like a small miracle. It is hard to explain that feeling without reaching for the dramatic, but it was simple. I was sitting with somebody who has inspired me to do my best with my own skill set every single day.

In my humble opinion, Brother Shabazz is the Gordon Parks of this generation.

We met in Dr. Ronald McNair Park, across from the Brooklyn Museum, with the Botanic Garden close by and Eastern Parkway doing what it always does, feeding the city into itself. Brooklyn kept interrupting our conversation the way it interrupts everything. Trucks. Traffic. Sirens. I record outside a lot, and the city always wants a speaking role.

Jamel looked good. Peaceful. Ready. Earlier that day, he told me he had met with a designer about a new book, Our Sights in the City, a street photography project built around work the public had never seen, work he was excited to bring into the world. He described it like a new endeavor that would carry him forward. The way he said it made the years behind him feel alive, like they were still in motion.

When you talk to someone whose work has become part of the visual vocabulary, you start to understand something most viewers never get to see. The images feel inevitable once they exist, but the person who made them had to choose a life that could hold them. Jamel’s life holds them. His story holds them. His values hold them.

He told me he learned the “science of the decisive moment” early, and he tied that lesson to a critique that still sits in his chest like a tuning fork. He had a stack of 36 photographs from the shop, and he felt proud. A family member looked at the first few and handed them back. They do not say anything.

It hurt. Then it helped.

Over time, he understood what the man meant. Images have to speak.

That phrase explains a lot about why his photographs land the way they do. Even when the subject is style, the photograph carries a sentence. Even when the subject is joy, the photograph carries a warning. Even when the subject is a pose, the photograph carries an ethic.

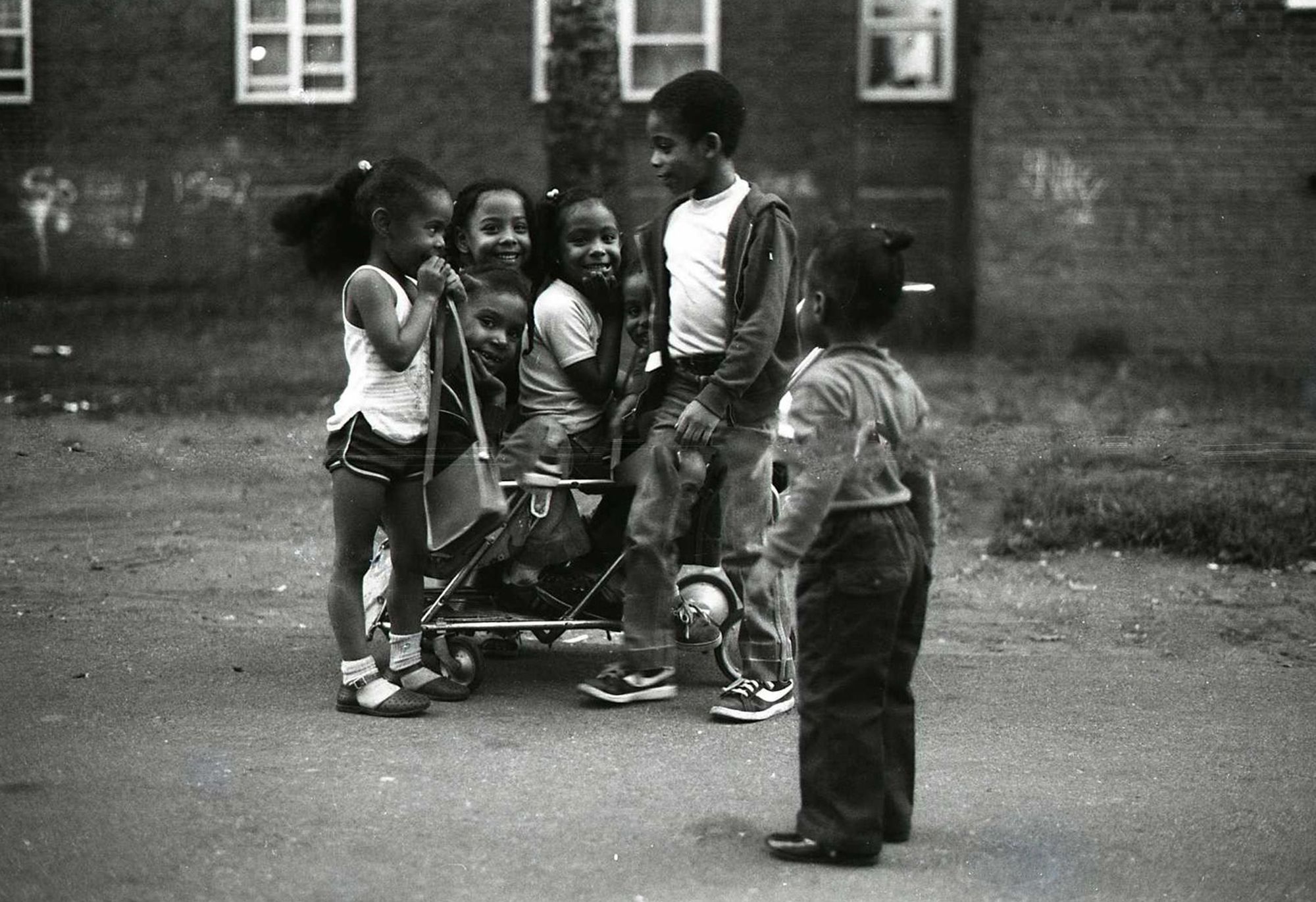

His early Brooklyn life sat inside a different kind of sentence. He was born and raised in the Red Hook projects, a Vietnam-era childhood that he remembers as family oriented, full of parks and activity, full of innocence. He described the canal, the three-line parks, an Olympic-sized pool and stadium, and the feeling of being a kid in a neighborhood that still had room for kids.

Then Vietnam came closer. He remembers the first young man from the projects killed in 1967 and the way the grief moved through the buildings. He remembers veterans coming home and playing drums in the park as therapy. In his voice, you can hear how a child absorbs these things, how early awareness forms in the background while you are still learning how to be a person.

He also remembers the games. He described one kids invented called Coco leivo, a two-team game built around bases, territory, capture, rescue, and those concrete tables that become rules when childhood has to improvise a world. Listening to him explain it, I kept thinking about how city kids learn patterns early. Movement. Strategy. Group psychology. The unspoken laws of a block. You learn how to read faces. You learn when to run. You learn when to stand.

His father shaped him as much as the projects did. Jamel described him as deep, brilliant, and unusually positioned for his era. His father enlisted in the Navy at 17, and to Jamel’s surprise, as a Black man in the 1950s, he was given a position as a photographer. He traveled, served for years, then came home carrying that broader world back into a Brooklyn apartment, building model airplanes and ships, doing graphic design, living in crossword puzzles, living in curiosity.

The house had a library full of powerful books, and Jamel talks about it like a doorway he walked through and never walked back from. One book sat on the coffee table and changed him early. It was called Black in White America. He was eight or nine, turning pages and seeing race in America in a way Catholic school never served him. He remembers looking up words he did not understand, writing them down, trying to decode what he was seeing.

He also remembers reading Playboy as a kid because his father had a subscription and he wanted knowledge wherever it lived. He describes being pulled in by the articles, by Alex Haley as an interviewer, by the first time he read about Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., by learning that John Wayne was a racist, by watching childhood heroes collapse under adult information.

When Jamel says he had a thirst for knowledge, he means a thirst that could not wait for a teacher to pour it.

Then the family structure shifted. In 1975, when he was 15, his parents divorced, and he, his brother, and his sister moved with their mother into a one-bedroom apartment. He described the economic pressure and the sense of burden he felt. At 16 he decided to enlist, and at 17, with his mother signing him in, he entered the Army. His father was against it, shaped by his own military experience and by what Vietnam had done to the younger men of his generation. Jamel went anyway.

He went to Fort Dix for basic training and describes it as a cultural shock. He was the youngest in his platoon, stripped down into the uniform sameness of the military, then exposed to how much prejudice and division still survives inside “sameness.” The war had ended in 1975, he went in 1977, and the drill instructors were Vietnam veterans.

He remembers cadences that made war sound plain. One drill sergeant loved to sing, and one cadence in particular landed like a brick: “We’re gonna rape, kill, pillage and burn.” That was when war stopped being television footage and started being a lived possibility.

He also remembers racism and white supremacists entering the military in the 1970s, and the North-South hatred that ran through the ranks, Black and white, like a second chain of command. He described the military as a microcosm of society, conservative, deeply political, and deeply revealing.

Germany brought another lesson, and also a lifeline.

Phil Harris was one of the first men he met when he was stationed there, and Jamel credits him as someone who saved his life. Harris did not smoke or drink. He read. He exercised. He traveled. He introduced Jamel to photography, to developing, to a routine built around elevation. Jamel describes being in a unit saturated with heroin, a drug epidemic on bases throughout Germany, with overdoses clustering around payday, and he frames Harris as the reason he stayed away from that lane.

When he says “saved my life,” it does not sound like a metaphor. It sounds like a measurement.

Then came the return to Brooklyn, and the return carried a kind of grief he did not fully see coming.

He told me that when he thinks about coming home, “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five comes to mind. He had already gotten word in Germany that younger brothers of friends had been murdered. He came home feeling good, then realized he had come home to what he called a war zone, with division and crews in a way he had not left it.

He frames that shift through consciousness. He remembers 1977 as a strong year, with Roots helping produce pride and identity among young Black men. He came home and felt that spirit had faded, and he looked around and realized people were no longer talking about the struggle.

So he went looking for the why.

He traveled to his old high school, Samuel J. Tilden, and started speaking with younger brothers, trying to understand what was happening. He compared his feeling to Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Happening Brother,” coming home with that vibration, trying to make sense of what he was seeing.

Then he said something that explains an entire era of his work in one sentence: the camera gave him the key. It became the entry point that allowed him to connect with brothers who were at war with each other.

He described walking major strips like Church Avenue, seeing brothers on corners with Pumas and Gazelles, the exact look you see in his images, then forging relationships across crews that had beef with each other. When I asked how he established that connection, his answer came from love and positioning. He was home. He loved his brothers. He saw many of them as little brothers. Some knew him before the Army as an older brother who was proactive in the community, consistent, affirmed in his convictions, determined to make a difference.

The way he approaches people has always mattered. He described stopping on the corner, speaking first, then asking, “Brother, can I pitch you brothers?” He would tell them they looked great, take the photographs, then build friendships that lasted for years.

A lot of people focus on the poses in Shabazz photographs, the way style becomes architecture. Jamel sees the poses as part of the creative process, built through collaboration, sometimes his idea, sometimes theirs, always designed to reflect who the subject is and what the moment carries. He wanted swagger, strength, personality.

Then the process turned playful and competitive. He describes it like a battle of the poses, each new group trying to outdo the last, inspired by what they had seen him photograph before. That detail matters because it reveals what his images often miss in retrospective conversation. His subjects were shaping how they wanted to be seen, and he was giving them a stage that felt respectful.

His respect extends beyond aesthetics. For him, photography sits inside community service. He talks about photographers and visionaries having the ability to make people feel good about themselves, to approach someone with sincerity and name their beauty, to offer dignity as a form of care. He encourages photographers to communicate, to take time, to give back, to go into schools, to redirect young people from shooting with guns to shooting with cameras.

His idea of “speaking images” lives in his process too. He explained that he looks with his two eyes first and asks a simple question: does this situation have something to say? If it does, he raises the camera and looks through what he calls his third eye, then composes and shoots. He shoots with purpose.

He gave examples that reveal how layered that purpose can be. In work like Pieces of a Man, every photograph carries meaning, sometimes through the subject, sometimes through what sits behind the subject, like graffiti tags or a political statement, the background speaking alongside the foreground. He wants the sequencing to feel narrative, like each photograph belongs where it sits.

His love of the subway fits neatly into that philosophy. He described the train as an alternative to the street when weather shifts, and he described using fast film and a wide aperture to work with available light, moving car to car, switching trains at major stops like Atlantic Avenue, riding like a fisherman. He loved the trains because the subject is stationary. The approach becomes calmer, more conversational, and the world above ground shows up below ground too.

His self-assignments show the same impulse toward witness. He talked about photographing the Bowery and prostitution after seeing alcoholism and poverty downtown, then spending time in a park on Christie Street, trying to understand the best way to document that world. He described a confrontation where he was surrounded by a pimp and some of his boys who intended bodily harm. He and his partner went back-to-back in a stance ready for war.

Then Jamel spoke his purpose out loud. He told the pimp he was a documentarian, documenting conditions to educate young girls about the horrors of prostitution. The pimp heard something in his voice and gave him the green light to come back and photograph.

Jamel’s takeaway from that story sits in a rare place. He admits he learned the “smoothness” of approach from the pimp, then repurposed it into a respectful way of engaging subjects. He also believes that time, conversation, and care helped get many women off the street.

In 1983, he entered another world built around containment and harm: he took a correction officer job at Rikers Island, and he did it at the exact moment crack hit, which made him a witness to the epidemic from inside the system. He worked at a youth detention center housing pretrial detainees, sixteen to twenty years old, and he described entering an environment of hatred and war, including brutal conflict between Black and Hispanic inmates.

He went in prepared. Before the job, he read George Jackson’s prison letters, read about Attica, watched Short Eyes, and carried personal knowledge of men from his community arrested for crimes they did not commit. He framed his position as an assignment, a duty aimed at helping save young men. He talked about bringing in books, educating, counseling, and using Malcolm X’s transformation as a living example of how a person can elevate while confined.

Even the way he partnered on the job reveals his commitment to balance. He made it a point to work with Latino officers so there was cultural understanding and language access inside an environment where conflict was rooted in culture, music, and identity.

If you listen to his life in order, you hear a repeated theme: he keeps stepping into situations that most people avoid, and he keeps stepping in with tools that can soften something hard.

Publishing is one of those tools, and his career in books mirrors his approach to the street. It is built on consistency, autonomy, and a long view.

He told me he initially approached PowerHouse because he was new to the publishing game, and they were producing art books and looking for new artists. In 2000 he approached them with an idea built around his series Back in the Days. The book came out a year later, in September 2001, and his strategy became simple: a book every two years.

He named the sequence the way a man names milestones: Back in the Days, then The Last Sunday in June, then A Time Before Crack, then Seconds of My Life. He pointed out that many of his books deal with time.

Later, as things slowed and the industry shifted, he moved into self-publishing. In 2010 he created Represent, a project that brought him into digital photography, and he entered it into the Photo District News book contest. It won first prize.

He talked about his self-publishing with the same clarity he brings to street work. He takes his money and reinvests it in himself, staying creative without anyone dictating the product he creates.

Then he spoke about Pieces of a Man as a book close to his heart, inspired by Gil Scott-Heron’s album title and released as a limited edition of 500 copies, in collaboration with Voices magazine. The way he described it carried an old-school pride, the pride of someone who knows how much labor sits behind a physical object.

His relationship to representation becomes even more visible when the culture tries to interpret him.

We talked about the moment he learned there was a character in Luke Cage meant to represent him. He said he felt baffled and bittersweet. He appreciated the honor, and he felt hurt by the way the character’s language diminished his essence, by the inaccuracies, by a portrayal that missed the care he brings to the street.

He is keen about being represented accurately. That concern is deeper than ego. It is about preserving a method. It is about preserving an ethic.

His relationship to commercial work carries the same boundaries. He told me about a campaign that left him feeling disrespected by a creative director, then explained why a later Puma campaign felt different. Puma assured him they would work with him, they gave him creative control, and he was able to incorporate props that carried a 1970s feel, including boom boxes and other details that matched his visual language. He described the joy of taking time, building a situation without a rush, and he contrasted it with the brief relationships that often shape street photography, where a shot can come together in minutes.

Then the conversation moved toward preservation, and his voice shifted into something I would call legacy-minded, with a kind of calm urgency.

I asked him about being inducted into the Smithsonian, and he traced his motivation to The Book of Eli. He said he watched it and saw himself in it, a man carrying something sacred toward an institution that could protect it. He described being blessed to document history and culture since the 1970s, and he felt that work belonged in the Smithsonian Institution, for future generations. He proposed donating some of his work, they accepted it, and a year later it was included in the archives of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

He described the relief of knowing that if he leaves this planet, his community will still be represented in an institution built to preserve memory. He also described a larger goal: to make sure the full body of work is preserved in museums and institutions, because he believes his work belongs in museums, accessible to people, protected from disappearance.

Then he zoomed out, the way elders do when they have lived through multiple versions of the same national cycle.

He said sometimes society feels like the Titanic, going down, and he talked about elections, Reagan’s era, the war on drugs, the war on people of color, the sense of social progress being reversed. He did not say this to collapse into despair. He said it as context for his commitment. As long as he has breath, he intends to inspire positive change, within his family and the human family of the planet Earth.

Sitting across from him in that park, with Eastern Parkway nearby as a literal conduit into the heart of Brooklyn, I kept thinking about how fitting that location was. He spoke about Eastern Parkway as the entry point that brings you into Clinton Hill, Crown Heights, Brownsville, and he spoke about some of his deepest photographs coming from that strip because it holds the route of the West Indian Day Parade, a celebration of Caribbean nations and history.

A parade route is a kind of living archive. People come out wearing memory. People turn identity into color and sound. Photographers come out trying to keep up.

Jamel came out for years.

He talks about his work with a steady confidence that never slips into performance, and that steadiness matters. His photographs carry love, and love can get sentimental fast. His photographs avoid sentimentality because his love is rooted in witness and responsibility.

He keeps returning to the same core belief: images should say something. They should carry a statement, direct or indirect. They should hold meaning, even when the viewer only feels the meaning before they can name it.

When people call his work iconic, they usually talk about the clothes, the stance, the swagger. He respects that. He also knows the deeper story: the relationships behind the frame, the respect behind the approach, the conversation behind the shot, the conviction behind the archive.

He has lived through the Vietnam era, through crack, through losses, through cultural shifts, through moments of public pride and private disappointment, and he keeps doing what he has always done. He looks. He approaches. He speaks. He makes the image. He gives something back.

That is why I trust the photographs. They come from a man who stayed close to people, close to history, close to the block, close to the consequences.

When I left the chess table that day, Brooklyn was still loud. It felt right. Jamel’s work has always held the sound of the city inside the frame, even when the photograph is silent. And if you listen closely enough, you can hear what the images have been saying the whole time.

They speak.

More About Jamel Shabazz

- Official Site – http://www.jamelshabazz.com

- Instagram – https://www.instagram.com/jamelshabazz/

- Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/Jamel-Shabazz-16841597946/

Shop for Books by Jamel Shabazz

- Back in the Days – http://amzn.to/2f2MxIc

- The Last Sunday June – http://amzn.to/2gcrRJJ

- A Time Before Crack – http://amzn.to/2fNVx2W

- Seconds of my Life – http://amzn.to/2gy0i1I

- Pieces of a Man: Photography of Jamel Shabazz: 1980-2015 – http://www.artvoicesartbooks.com/shop/51k7s88fwm6869fxpfenq2lmkhj9yd

Links from the Conversation

- West Indian Parade – http://wiadcacarnival.org

- Eastern Parkway – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eastern_Parkway

- Brooklyn Museum – https://www.brooklynmuseum.org

- Brooklyn Botanical Gardens – http://www.bbg.org

- 55 Stunning Botanical Gardens You Really Need to See Before You Die – https://www.sproutabl.com/gardening/botanical-gardens/

- Powerhouse Books – http://www.powerhousebooks.com

- Black In White America, a book by photojournalist Leonard Freed – http://n.pr/2fBF0fK

- Alex Haley: The Playboy Interviews – http://amzn.to/2fBzdXB

- Platoon (1986) – Rotten Tomatoes – http://bit.ly/2flyJna

- Marvin Gaye (Song) – What’s Happening Brother – http://bit.ly/2gi63Oe

- Luke Cage – http://bit.ly/2fZ2Jal

- Puma – http://bit.ly/2fBArBT

- Delancey Street – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delancey_Street

- Rikers Island – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delancey_Street

- Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson – http://bit.ly/2gi5R1x

- Short Eyes (Film) – http://bit.ly/2fnwIKR

- Attica Correctional Facility – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attica_Correctional_Facility

- Crack Cocaine – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crack_cocaine

- Self Destruction (Song) – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jxyYP_bS_6s

- The Central Park Five – http://www.pbs.org/kenburns/centralparkfive/

- Sam Cooke – A Change Is Gonna Come (Official Lyric Video) – http://bit.ly/2fnInZN

- Book of Eli – http://bit.ly/2ge0xyl

- Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture – https://nmaahc.si.edu

Comments 10